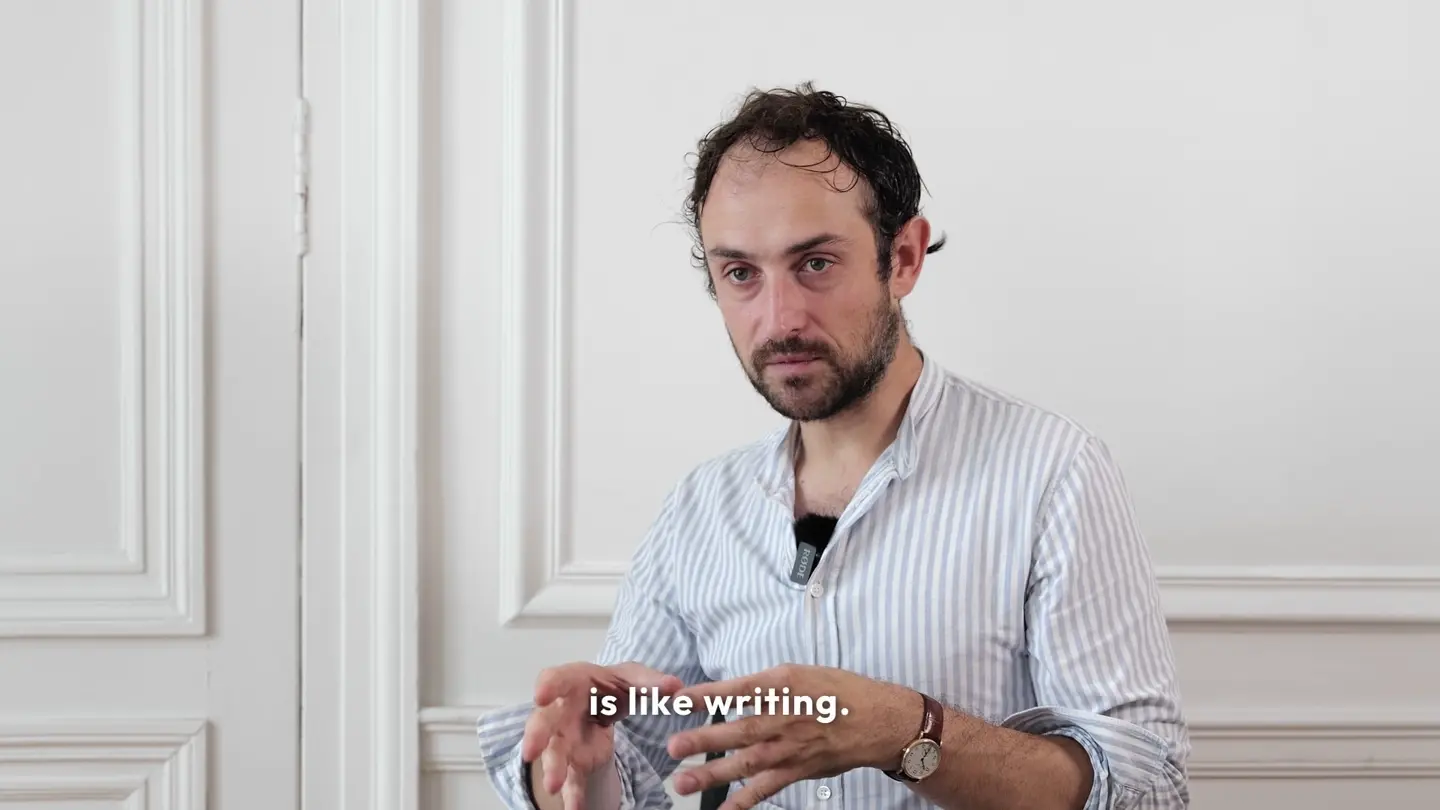

In Conversation:

Édouard Elias and Thomas Hoepker

To mark Leica’s 100th anniversary, Leica Gallery Paris is exhibiting images by photojournalist Édouard Elias together with ones by Leica Hall of Fame inductee and self-proclaimed “image maker” Thomas Hoepker, starting in September.

Introducing series production of the first 35mm camera provided photojournalists with a tool that enabled the greatest degree of discretion and flexibility for reporting. The reportage genre quickly grew to one of the most important pillars of Leica photography. Two prominent exponents, the French photographer Édouard Elias and Leica Hall of Fame inductee Thomas Hoepker, engage in a photographic dialogue at Leica Gallery Paris. Their photographs give us insight into the war zones and conflict areas around the world, while evoking memories of important moments in history. With this exhibition, the Leica Galleries are continuing their centennial concept where contemporary photography is juxtaposed with the work of a Leica Hall of Fame inductee.

Leica: 100 years of Leica photography – what are your thoughts on this?

Édouard Elias: The first Leica marketed in 1925 was a lightweight tool that allowed multiple shots to be taken without needing to change the film. This marked the birth of a tool for photojournalists wishing to capture a specific reality at a precise moment. For many years, Leica chose to preserve its M-System to uphold a particular shooting practice, rooted in classic focal lengths and anticipatory composition. For Leica photographers, this means being part of a photographic movement that has spanned over a century.

How has the work of LHOF winners influenced your work?

What are the similarities or differences that become visible in this dialogue?

These artists not only redefined the rules of photography, but they were also pioneers in capturing raw emotion and truth, using technical yet simple skills to achieve precision. Their work taught me to observe the world around me with greater sensitivity, to refine my behaviour towards my subject, and never underestimate the power of a single frame. Furthermore, these photographers’ technical approach has also encouraged me to work more instinctively with my own Leica camera. Their commitment to photography as a means of documenting history continues to this day.

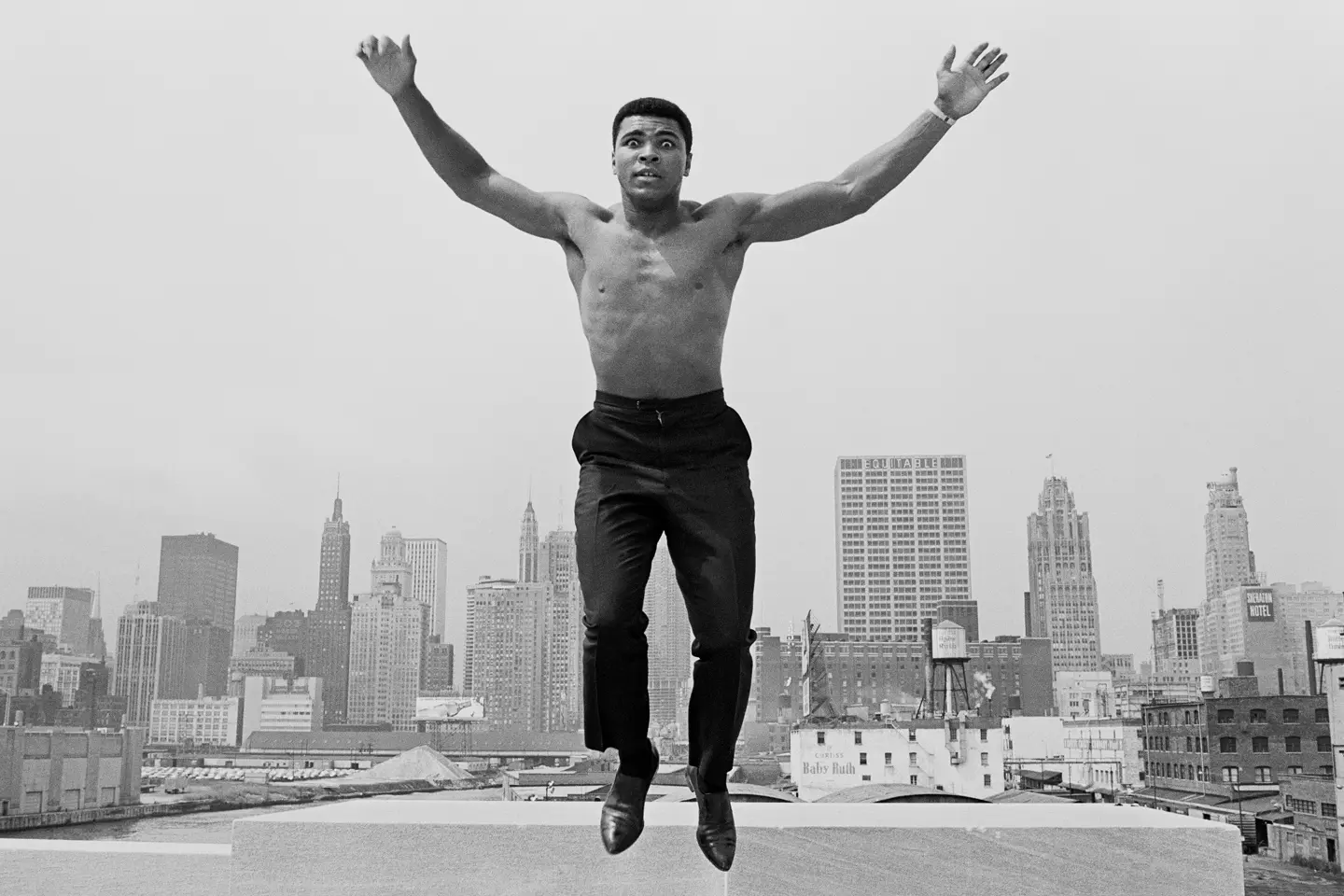

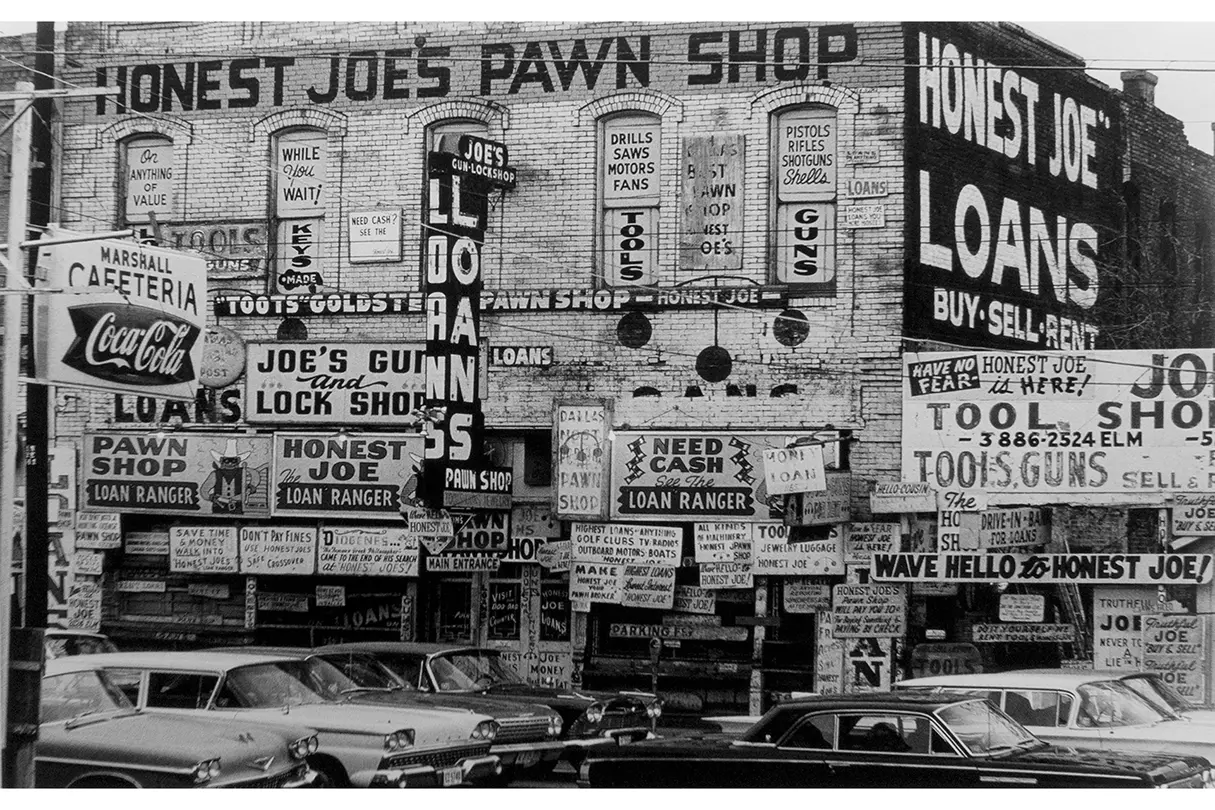

© Thomas Hoepker und Magnum Photos

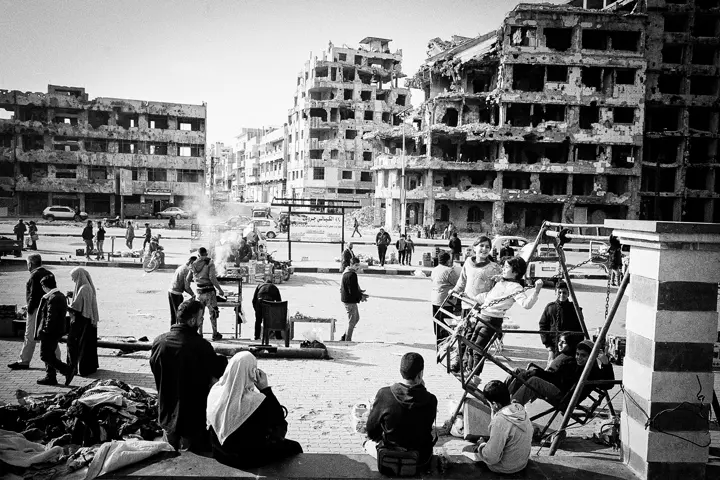

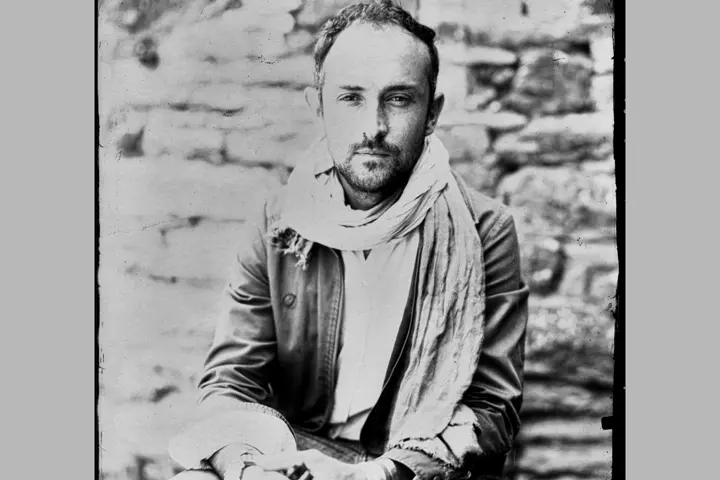

© Elias Edouard

What is the subject matter/theme of your photographs that are being displayed in the exhibition?

The images come from my work in Syria after the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in 2024. The project is titled Syria, Year 0. It documents the traces left by over a decade of war: abandoned prisons, destroyed cities, the remains of power structures, and physical and symbolic absences. It’s a journey through ruins, without visible captions, questioning what remains when a regime collapses.

The exhibitions revolve around a visual dialogue between two generations. How did you approach this theme?

This dialogue is not so much about generational opposition as it is about continuity in the way we look at the world. Thomas Hoepker and I worked in very different contexts, but we share the same demand for clarity and distance. Tools, eras, and media may have changed, but certain gestures and ways of being in the world and positioning oneself in relation to it remain. That form of craft, almost artisanal in nature, seems to transcend generations.

Where do you get your inspiration?

I draw as much from literature and history as from photography itself. Writers like Curzio Malaparte, Joseph Kessel, Émile Zola, Thucydides, and W.G. Sebald haunt me just as much as war photographers’ works. What they share is a rigorous way of observing and describing without shying away from the complexity of reality. Photography is a form of writing, and like any form of writing, the richer the visual vocabulary, the more one can break free from established models to build a personal syntax. I find inspiration in that diversity of styles, narratives, and approaches in order to construct my own photographic language, one that seeks to tell stories without simplifying, to convey insight without imposing.

© Elias Edouard

What camera did you use and why?

For this project in Syria, I primarily used a Leica MP loaded with Kodak Tri-X 400 black-and-white film, paired with a 28 mm lens. This setup ensured discretion, durability, and precision in unstable environments. Shooting in black and white with analogue film enforces a certain slowness, disciplin,e and economy – it changes how one sees. It also connects the work to a visual tradition in documentary and war photography from the 20th century. Through this aesthetic, I wanted to evoke the recurrence of human catastrophe, totalitarianism, industrial devastation, societal collapse – all of which Thucydides identified as tragic constants in human history.

How do you think photography has changed in recent decades?

Photographic tools have become entirely embedded in everyday life. With smartphones, we now carry a kind of ‘super-device’ around with us everywhere – all that’s missing is a built-in coffee maker. The line between classic photography using a dedicated camera and casual image-making with a phone has become blurred.

This democratisation has fundamentally changed our relationship with images: they are omnipresent, immediate, and often ephemeral. It has transformed our perspectives, our production methods, and even our belief in photography as a medium. But this ease of access also has its drawbacks: it has blurred reference points, weakened formal rigour, and led to a normalisation of visual aesthetics. What continues to matter – and will always matter – is the intention behind the image. That is where the difference still lies.

© Thomas Hoepker und Magnum Photos

What opportunities and challenges do you see for the future of photography?

One major challenge is the homogenisation of photographic production in the digital era. The volume of images being produced is overwhelming, but photographic culture hasn’t always kept up. We’re seeing a flattening of aesthetics and standardisation when it comes to post-processing. In the past, technical constraints, the choice of format, as well as the specific film and camera used, forced photographers to push themselves. Every tool imposed its own rigour, rhythm, and method. Today, anything is possible, and that abundance can be disorienting. It often results in repetition, thereby creating a visual comfort zone. The opportunity still exists, however, to find one’s own voice within the noise, to take the time to think through the image and to remember that photography is not only a matter of technology but one of intention.

What role do galleries play in the age of digital media, and specifically for your work?

Galleries offer a true sanctuary of peace and stability, a space where we can rediscover images in their most authentic and timeless form. For me, a successful photograph is the result of a balance between the shot and the print – an alchemy where the print matters as much as the moment the image is captured. While digital photography is effective, it cannot convey the same emotion as a physical object that endures the test of time, like photogravure essays or a traditional analogue print. In a gallery, the image takes on its full dimension: its size, its placement, and how it interacts with the surrounding space all contribute to the visual experience. In contrast, on digital platforms, it’s often algorithms or image editors who determine how the work is presented, and we lose that direct relationship with the image in its entirety.

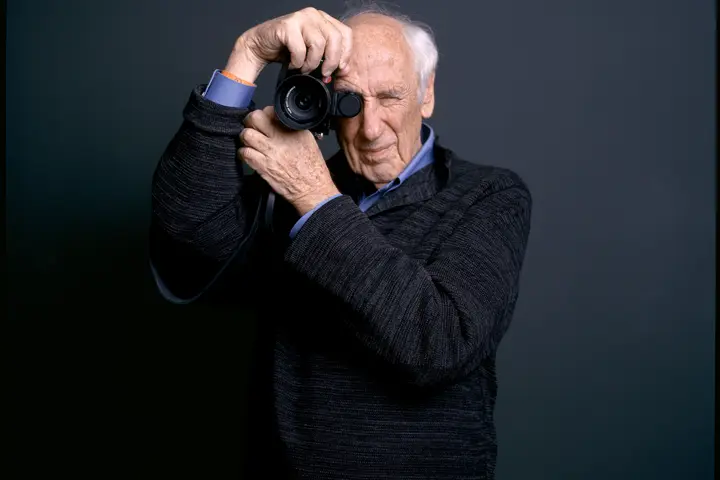

© Sebastien Bergeron

Édouard Elias

Born in Nîmes in 1991. After spending ten years in Egypt, Elias returns to France and studies photography at the École de Condé in Nancy. After doing a reportage on a refugee camp in Turkey, he began to document the Syrian civil war. He is held captive for ten months there. His work has appeared in Der Spiegel, Paris Match ,and Sunday Times Magazine.

© Arne Wesenberg

Thomas Hoepker

Born in Munich in 1936. Early successes and awards. Photo reporter for Münchner Illustrierte in 1960; as of 1962, he is a member of the Kristall editorial team and then works for Stern as of 1964. In addition to black and white pictures, Hoepker produced early colour pictures for the magazines. Here too, his Leica is his indispensable work tool. Starting in the 1970s, he also worked as a cameraman, producing numerous documentaries and TV movies. Hoepker moved to New York in 1976, and, from 1978 to 1981, was the Executive Editor of the American edition of GEO. He returns to Hamburg and works as Art Director in the chief editorial team of Stern. In 1989 he became the first German member of the renowned Magnum Photos Agency, acting as its President from 2003 to 2007. He produces further documentaries with his second wife, the filmmaker Christine Kruchen. He is the recipient of numerous awards, including the Culture Prize of the German Photographic Society (DGPh) in 1968. In 2005, thousands of photographs are donated to the Photography Museum of the City of Munich. In 2014, Hoepker was honoured with the Leica Hall of Fame Award. After a long illness, he passed away on 10 July 2024 in Santiago de Chile.