In Conversation

Marking the occasion of Leica’s 100th anniversary, Johanna-Maria Fritz speaks about the work of Leica Hall of Fame winner Jürgen Schadeberg at the Leica Gallery Munich.

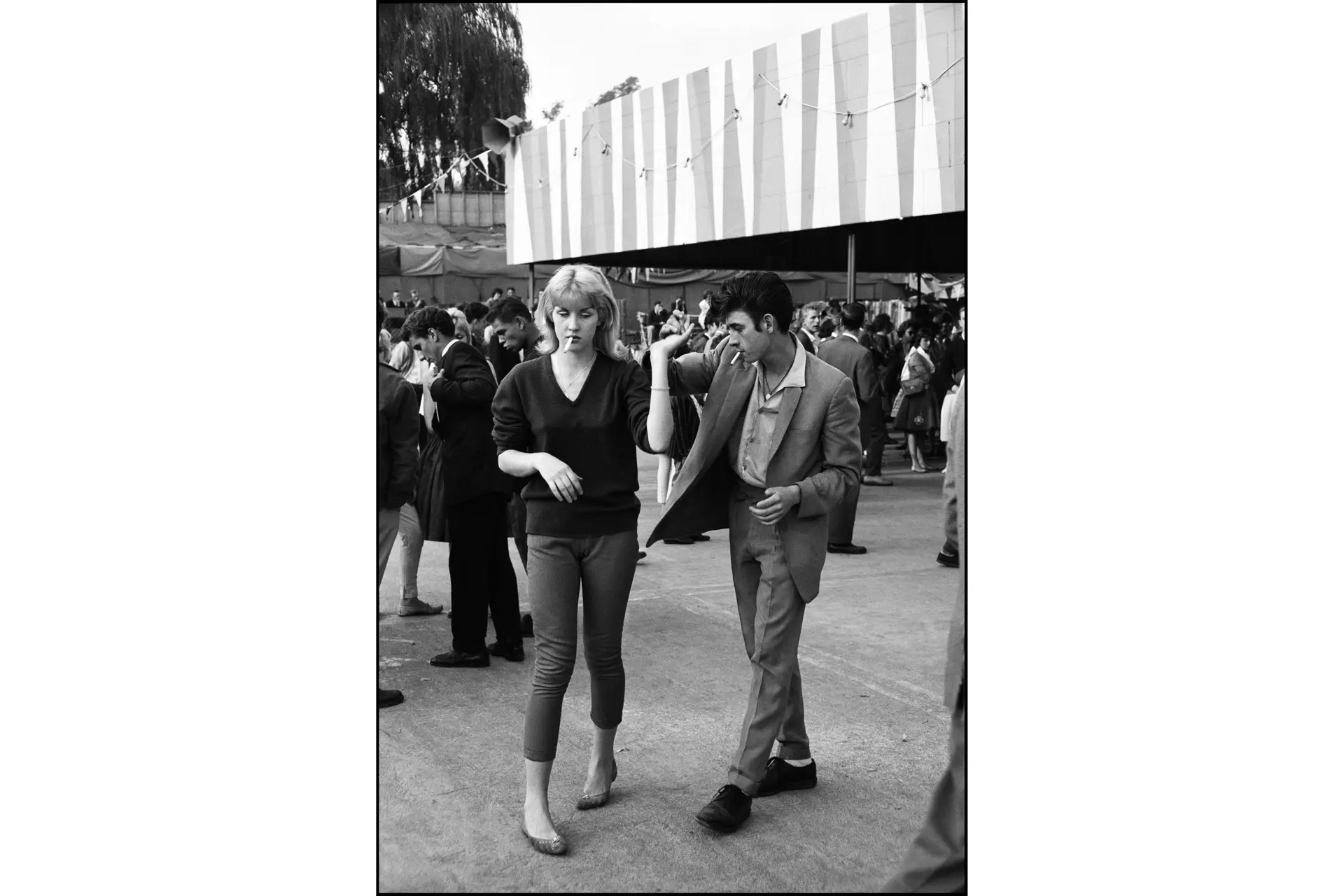

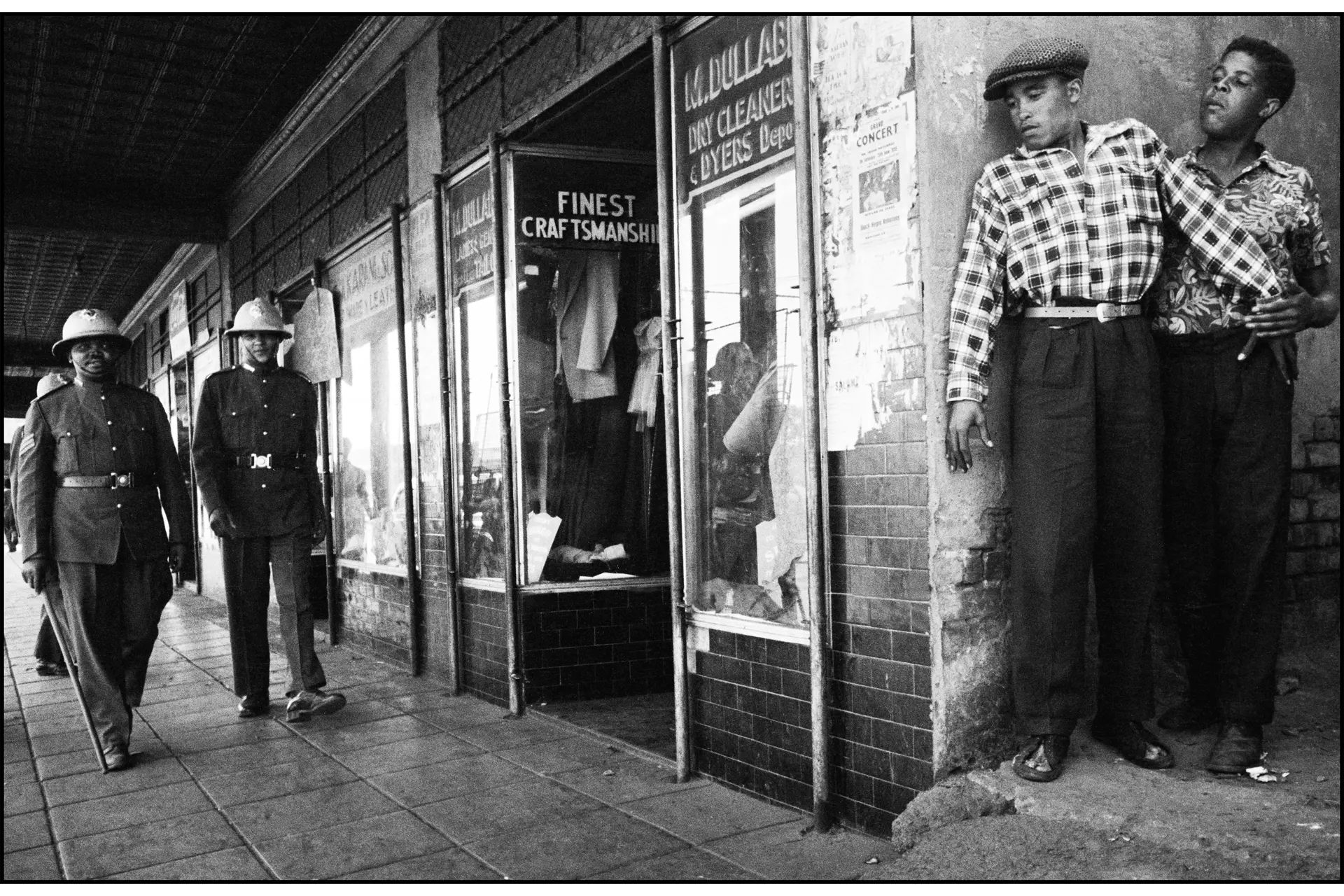

Within the framework of Leica’s centenary celebrations, a new exhibition will open each month during 2025 at a selected Leica Gallery, bringing together a contemporary talent with a Leica Hall of Fame (LHOF) award-winner. On April 14, the Leica Gallery in Munich will host a dialogue between Johanna-Maria Fritz and the work of Jürgen Schadeberg. The two photographers share a sense for places and people impacted by social and economic upheavals.

100 Years of Leica photography – what do you think about that?

Johanna-Maria Fritz: Leica has a long and multi-layered history. During the Nazi era, the company was partly integrated into the war economy and at the same time there was the ‘Leica freedom train’, a secret rescue operation with which Ernst Leitz II and his daughter Elsie Kühn-Leitz helped Jewish employees to escape – often with a Leica to enable them to make a living abroad as photographers.

Even though Leica was often associated with male photographers, such as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa, many women have also produced outstanding work with a Leica. With their Leica perspective, Inge Morath, Gerda Taro, Dorothea Lange and Jane Evelyn Atwood shaped photography history just as profoundly.

My personal relationship with Leica began with an M6. On my 18th birthday I received money to get my driving license, but bought a used Leica M6 for 600 euros instead. That was my first deliberate choice for a camera, and it still accompanies me to this day.

How has the work of LHOF winners influenced your work?

The work of LHOF winners has had a significant impact on my perspective as a photographer. I am especially pleased that Herlinde Koelbl and Barbara Klemm have received this award. Their images have accompanied me throughout my career, shaping my understanding of storytelling and visual depth.

I remember being at Barbara Klemm’s exhibition at the Gropius Bau in Berlin, when I was a young photographer. Somewhere, I had heard that she was often seen as non-threatening or even underestimated. That resonated deeply with me. As a woman, it is often easier to gain access – people let their guard down. I share that experience and see it as both an opportunity and a responsibility in my work.

What are the similarities or differences that become visible in this dialogue?

Jürgen Schadeberg and I share a commitment to documenting history and human resilience. His work captured South Africa’s Apartheid era, focusing on oppression and resistance, while I explore marginalized communities and conflict zones globally, often highlighting women’s experiences. Though our styles reflect different eras, we both use photography as a tool for storytelling and change. This exhibition creates a dialogue between past and present struggles, showing how images can preserve history and give a voice to those often overlooked.

Where does your inspiration come from?

I differentiate between my independent documentary projects and my journalistic work. With independent projects, I spend a longer period of time working intensively on a topic, such as my current Keep Her Pure project, which deals with the idea of female virginity. I’m doing research in all directions. Not only through photography, but also through sound, text and video.

In contrast, my journalistic work often leads me to places where horrifying crimes are happening. I see it as my responsibility to document them and to educate about them. I approached the project I produced for Leica with more of a journalistic attitude than I do for my personal work. We only had two weeks, which I spent in West Virginia. I travelled through the area with a journalist friend, spoke with many people and explored many places.

What is your series about?

It’s a story about America’s fading coal boom; about what happens when a region loses its main industry; about the people who don’t want to be forgotten. In the middle of the last century, around 125,000 people worked in the coal mines of West Virginia in the east of the USA. Today it’s only 13,000. Once thriving coal settlements have become ghost towns. Rhodell is one such case. Where cinemas, ice cream parlours and gas stations once stood, you now only see overgrown ruins. Even so, about 130 people still live there. 34% of them live below the poverty line.

Which camera did you use and why?

The Leica SL3. I wanted to use a full-frame camera with autofocus, and have the possibility to change lenses.

How do you consider photography has changed over recent decades?

There was the transition from analogue to digital, of course. Ten years ago when I was studying, I still photographed a lot with analogue. Films were expensive back then, but not as absurdly expensive as today. I simply can’t afford to work analogue for bigger projects. What’s more, digital medium-format cameras have changed the game. They open up very new possibilities.

How do you assess the current situation for photographers?

I believe that photojournalists are extremely important right now. Fake pictures are generated with AI and fake news spread at top speed through social media. That’s why we are tasked with making the truth visible.

However, many media companies are trying to save on costs. Major newspapers are increasingly paying flat rates for reporting from war zones and reducing the already low daily rates. At the same time, the cost of living is rising. This worries me.

What role do galleries play in the age of digital media, and specifically for your work?

I think exhibitions are essential, whether in galleries, museums, or even on outdoor walls. Seeing real prints instead of just experiencing images on a phone or computer allows for deeper engagement with a photograph.

At the same time, visiting a museum or gallery is often something very elitist. Outdoor exhibitions or even the internet make it possible for people from all social backgrounds and from all over the world to see images. Galleries still play a crucial role in my work, as they provide a space where my photographs can be presented in the way they were intended. And, of course, exhibiting in galleries is also part of how I make a living as a photographer.

Johanna-Maria Fritz

Officially speaking, Johanna-Maria Fritz lives in Berlin. However, in reality she travels most of the year. She studied photography at the Ostkreuzschule in Berlin and since 2019 she has been a member of the agency bearing the same name. Her work has been published in Der Spiegel, Die Zeit and National Geographic, among others. She has earned a number of recognitions, including the Inge Morath Award and the German Peace Prize for Photography. Most recently, she photographed in Syria after the overthrow of the Assad regime.

Jürgen Schadeberg

Born in Berlin, Schadeberg attended the School for Optics and Photo Technology there, after which he worked for the Deutsche Presse-Agentur (German Press Agency) in Hamburg. He moved to South Africa in 1950, where he worked until 1959 for Drum magazine, the most important forum for the black majority population. He documented the living conditions under the racist Apartheid regime and portrayed personalities such as Nelson Mandela and Miriam Makeba. He later returned to Europe and then went to the USA. In 2018, Leica Camera AG inducted him into the Leica Hall of Fame.